Links:

Fragments of memory, from a young man's reading of Orwell, I hoped would be

helped out by Simon Schama's last episode of The History of Britain,

called 'The Two Winstons'. These were Winston S Churchill and Winston Smith,

the fictional hero of Orwell's 1984, when Stalin has become Big

Brother.

Orwell allowed himself a comment on the bathos of the English class system,

with some common Smith calling their son after the aristocratic Winston.

One is tempted to change Winston Smith to Winston S Myth or Winston's

myth.

Churchill made an ill-humored post-war election speech notoriously warning of

the jack-boot from British socialism. The third of C S Lewis' classic SF

trilogy, That Hideous Strength ( 1945 ) is essentially based on this

idea that a political victory of the statists was almost as if Britain had

lost, rather than won the war.

From its inception, Churchill was notorious for his fulminations against bolshevism. In his War Memoirs ( 1933 to 1936 ) Lloyd-George regarded Churchill morbid in his attitude to that most mortality-inducing of regimes. This goes to show how easily the great man's opinion was discounted. Churchill had made less than no headway in persuading others. From the onset of the Revolution, he said that Russia had sunk into barbarism.

His warnings against Hitler were as thanklessly received. Lady Astor

regarded Churchill as a 'war-monger' for trying to prevent another war by

preparedness against an irreconcilable enemy.

A celebrated exhange is too good to omit. Nancy Astor said: Winston, if I were

your wife, I would put poison in your tea.

Churchill answered: Nancy, if you were my wife, I would take it!

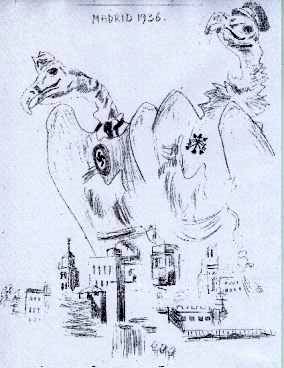

Schama summed up the first half of the twentieth century in Britain thru these two literary activists, Churchill and Orwell. He also illustrated the pros and cons of television documentaries: vivid, with well chosen period footage, but a sketch of a sketch of the times. His television outline of Orwell's life is like an artist's line drawing that conveys how much he knows of his subject by his choices of the minimal number of strokes.

Churchill and Orwell, from the top and bottom ends of the British ruling

class, were more often than not, at odds with it. Neither of them were party

men. They were distrusted by their respective 'sides'.

Thru-out most of the inter-war years, Churchill was 'a study in failure' to

quote another historian. He was considered yesterday's man. Churchill does not

represent the history of most of this period.

And George Orwell was a marginal figure on the Left. He was unpopular with the

Popular Front that included Left-wing tyranny against Right-wing tyranny.

Not until the second world war does Churchill represent history. Orwell does

not represent history, until the onset of the Cold War.

Ultimately, the man of the Right would be vindicated against the right wing

dictators, and the man of the Left against the left wing dictators.

Schama is justified in picking them as correctives, rather than

representatives, of twentieth century history.

Simon Schama began his program with the swinging sixties when all they could

say to the past was: good riddance to it. Then came Churchill's state funeral.

( Churchill himself had planned for it, like a last campaign, an Operation No

Hope. ) Then, Schama was a history student, deeply influenced by Orwell. Schama

alludes to the nation's out-pouring of grief, in terms of when 'the snivelling'

was all over.

Schama's dismissive cynicism is pure Orwell.

This pure Orwell, that Schama characterised in a remark of his own, is the

bitterness of a betrayed idealist. In his first novel, Burmese Days (

1935 ), disillusion with the Empire is over-shadowed by despair over the woman

who deserts the character, based on Orwell's experience as an Imperial

police-man.

Orwell was to say he found the Burmese Buddhist monks particularly trying.

Apparently, they were the only example in Asia of a highly politicised Buddhist

clergy, and of a particularly antagonistic kind.

The jilting woman's shallowness, however, only emphasises that of the whole colonial culture. The suicide of the jilted man, after a night's torment in which he even perceives her for what she was, symbolizes the death of Orwell's imperial ideal.

Orwell's personality is already marked in the first novel -- the biting and dismissive judgements on frailties -- the satirist with a leaning to tragedy, rather than comedy, in the human condition. This links to his political commitment: maybe he feels humorous tolerance of human failings is too indulgent of the world's wrongs. He once declared English writers' sense of humour, as their 'besetting sin'.

Orwell said Burmese Days embodied his early aspirations to

literature, full of 'purple prose'. In my opinion, it is his best conventional

novel -- an esthetically satisying work, a work of art, in a way that later

novels are not. He put a lot of descriptive work into it, and it paid off.

Orwell retained a commitment to literary values, as in championing the

modernist poets, though, as he put it: most of them went politically wrong.

He criticised H G Wells for wasted talent. As others have said, Wells deserted

his books before they were well finished work.

Orwell's own novels, after Burmese Days, may not be free of his own

criticism. Orwell admitted he was no novelist. He turned to non-fictional

reports of his experiences in search of the working class. Some of these

encounters are to be found, as articles, in their own right, as well as finding

their way into his novels. Hop picking, when she finds herself on the road,

becomes one recourse of A Clergyman's Daughter ( 1935 ). This

character is another expression of Orwell's own up-bringing in genteel poverty,

where the parish church's thin congregation is visited, in summer, by the

sickly corruption of the entombed.

This was an early work, which was almost destroyed. It is perhaps not fair to

judge him by it, as a novelist. Orwell did destroy one of his novels. He

regreted doing so, because there was probably something there he could have

salvaged.

Keep The Aspidistra Flying ( 1936 ) alludes to the lower middle

class fashion of keeping this plant in their homes. The title suggests mock

heroics in the style of Cervantes but the novel is nothing of the sort. J B

Priestley was asked what he thought of various authors. 'Jolly Jack's'

one-liner for Orwell was: too much of a misery. This novel vouches for that,

more than any of his works.

Orwell had a similarly poor opinion of Priestley. A review belittled Angel

Pavement as holiday reading. There is often no love lost on the Left. In

Literature and Western Man, Priestley didnt mention Orwell.

Had the fictional police-man, in Burmese Days, given himself a

reprieve, he might have become the life-denier, who ill-graces Keep The

Aspidistra Flying. The contrast in story lines is that the former

character is doomed, and the latter is saved, by a woman. Until then, the

anti-hero seems determined to be more depressed than the Thirties Depression he

is half-living thru.

In the end, his girl-friend gives herself to him, when he is down. A corrupt

puritanism allows him a perverse satisfaction from not enjoying her. Yet things

are supposed to work out. The failed poet becomes an advertising jingler and

married life beckons.

Coming Up For Air ( 1939 ) is the last of Orwell's conventional novels, before the last two politically motivated out-breaks into fable and science fiction. The author re-creates himself as a different human being, which is perhaps the distinctive pre-occupation of novelists. Orwell is imagining himself as having another life, to the one he has had.

The main character is big and fat. He has children: watching over them on a night, sometimes, but not often, he feels he is nothing more than the husk of these wonderkind, redeemed in their sleep. ( Later, Orwell and his wife will adopt a child. )

In most literature, whether the writers have children or not, there is not much about them. Most novelists seem to think that children should be not seen and not heard. As David Lodge says:

Literature is mostly about having sex and not much about having children; life is the other way round.

The passion in Coming Up For Air has gone out of the narrative character's marriage and indeed his whole life. He seeks to re-kindle youth's joy of living by going back to his roots -- coming up for air. As the title hints, fishing was his boyhood passion. There was a deep, secluded, arbored pool, the haunt of pike like primeval monsters.

Orwell manages to infuse the reader with something of his passion for the

sport ( which, after all, stems from human need ).

I remember being thoroly bored by a fisher boy, eyes blazing, go on about his

pastime. I listened with as polite an interest as a youngster could muster, and

wished the girls, with who we played hide and seek, hadnt left for their teas.

Now I am not only bored but repelled and sympathise with Leigh Hunt's

extravagant condemnations of Izaak Walton.

Orwell used his writing talent for worthier causes. Indeed, the story fires an early warning shot in the conservation battle. The beautiful pool has been drained and filled with rubbish for a new building site.

The narrative character has sensibilities but he is not an intellectual. You couldnt say he was a working class man because there is none of the solidarity with mates working together in the factories. To say he was lower middle class would be to say he was isolated, and to that extent an individual. But not an educated individual.

He has an old public school teacher, of the classics, who tells him there

were ancient Greek tyrants, the spitting image of Hitler. ( Orwell received a

letter, about one of his novels, from a former teacher. ) A plebeian character,

such as Orwell tries to portray, wouldnt have had a 'public' school education,

which in England means a private education. But, in 1939, Orwell gets

across the fact that war-mongering is nothing new.

The bombing of some houses is implicitly believed to be the start of the coming

war. When it turns out to be an accident, this is regarded as nothing more than

a reprieve.

The story itself is a reprieve of age with a last visit to the haunts of one's

youth.

Orwell's documentary writings on the conditions of the poor are much more important than the pre-war novels. The first of these, Down And Out In Paris And London, was rated well-up in a book-shop top hundred list of twentieth century books. ( 1984 and Animal Farm took second and third places. ) This may be an exaggeration of its merit compared to the twentieth century's best writings ( mostly missing from the list ) but it is a fine book, never the less.

In Paris, Orwell worked in catering. Anyone who has been a washer-up will recognise the hectic hotel atmosphere behind the scenes. After a while, it tends to eject one like the contents of a pressure cooker. ( Hence, Harry Truman's remark: If you can't stand the heat, get out of the kitchen. )

Orwell lands in England to wander the country with the unemployed. He doesnt

join the ranks like the Jarrow March. Rather, he tags along with individuals,

finding out how they came to be down on their luck. With this book, one enters

into these forgotten souls' aimless walking the streets in the summer dust. (

Winter, of course, would have been much worse. )

One destitute man, he urges to take a bottle of milk from a door-step. For all

his hunger, he dare not do so, despite the fact that the bottle has obviously

been left by mistake at an empty premises. This incident opens one's eyes to

the paralysing severity of the law at that time.

The limited number of places, where shabby individuals can rest without being moved on, or thrown out, makes Orwell cutting about the phrase 'street-corner loafer.' 'The spike' is the last place they would rest up, if they had any other choice. Orwell finds himself ( the pitier ) the object of pity there, because his accent gives him away as a 'gentleman' presumably fallen on bad times. He wasnt too pleased at the misguided decency of this English class discrimination, tho it happened to be in his favor.

In Notes from a small island, Bill Bryson takes issue with Orwell's distaste for the standard of cleanliness he found at his lodgings, when writing his investigation, The Road To Wigan Pier ( 1937 ). But you only have to consider Alan Bennett's reminiscences, of a chip in the sugar and a cream cracker under the couch, to recognise Orwell's description is authentic.

Or, for that matter, the cartoon strip Andy Capp will serve. Capp lives a closed round of betting, boozing, bawdying and sporting. If he is one of the sea of bobbing caps driven in and fleeing out of the factory gates, the cartoon hardly shows it: Capp shuts out the trauma of labor from his consciousness. His cap is pulled down over his eyes, which we never see, seeing he has no sensibility.

His Missus, he may patronise, when caught in a good mood. As Capp always wears a cap, she always wears a head scarf, the symbol of her relentless domestic servitude to her do-nothing master, his intransigence being the standing joke that kept the cartoon going. Andy's put-down rejoinder was always punctuated by Flo's dopey-eyed aside at the reader, as she trots dutifully behind her lord.

'Married men live longer than bachelors,' Flo tells Andy.

'Serves 'em right,' retorts Capp.

No matter how hard a woman slaved to wash off the atmosphere of soot, ever undoing her efforts, a partner, who behaved at home like a sack of coals on her back, would as likely as not degrade her to a slattern.

Times have changed for some. In Germany, husbands are required by law to help with the house-work. ( As for the Andy Capp type, I doubt they would bother to throw him in jail. More like, they would bring back capital punishment! ) Germany apparently has domestic democracy as well as industrial democracy. Into the twenty-first century, Britain still hasnt the latter. Industrial partnership, between management and work-force, obviously would have been a better example for the marital partnership.

H G Wells gave the Penny Dreadfuls etc their due, as a gateway to

literature for the likes of Mr Polly. But Orwell pioneered essays in cultural

trivia such as the strip cartoons in the boys comics. He recognised what would

nowadays be called their sociological significance, their naive imparting of

attitudes or prejudices, instilled in young minds.

He exposed that for what it was. But he would have fought cultural and literary

censorship. Taxes often subsidise a left wing 'thought police' to tell the

public what is best for them. The 'thought police' is an insight we owe to

Orwell.

With respect to the enjoyment they gave in childhood, he would find value in a hack like Frank Richards, who, nevertheless, created in Billy Bunter, amidst his chums, a literary immortal of sorts. At the time, such sloggers of literature would not have been deemed worthy of academic notice. Richard Hoggart's The Uses of Literacy perhaps marks a turning-point in that respect.

The long and arduous hours of working people didnt leave much surplus energy for creative leisure. Orwell met an activist, who consciously channeled his bitterness at not being able to have children, into political agitation. With a family to look after, he wouldnt have had such energy to spare on aggression.

From the comfort of his departing train, Orwell left us with the view of a

woman's utter hopelessness, lost amongst the endless house rows, as she tried

to unblock a drain.

He seemed relieved to leave. The second part of The Road is a polemic

against doctrinaire socialism. Marxism for Infants is an example, he

imagines, of the latest doctrinaire text, sarcastically implying it is a fairy

tale compared to the bleakness he has just witnessed.

Orwell is guilty of his own strictures: the polemics of the second part are altogether inferior to his observations in the first part. It is a relief to speculate from having to take in the spectacle. That is not to say Orwell lacked commitment. Rather, the scale of the industrial depression offered no obvious means of remedy. The fight for republican Spain was an opportunity to do something for a working class government.

Richard Lung.

To top.