...It was a time of heroes, of saints, of martyrs, of miracles! Thomas Ó

Becket was murdered at Canterbury, but for more than three hundred years his

name lived on, and his bones were working miracles, and his soul seemed as it

were embodied and petrified in the lofty pillars that surround the spot of his

martyrdom. AbÚlard was persecuted and imprisoned, but his spirit revived in

the Reformers of the sixteenth century, and the shrine of AbÚlard and HÚloise

in the PÚre La Chaise is still decorated every year with garlands of

immortelles. Barbarossa was drowned in the same river in which

Alexander the Great had bathed his royal limbs, but his fame lived on in every

cottage of Germany, and the peasant near the Kyffhńuser still believes that

some day the mighty Emperor will wake from his long slumber, and rouse the

people of Germany from their fatal dreams.

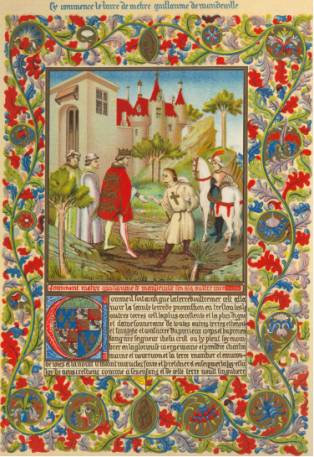

We dare not hold communion with such stately heroes as Frederick the Red-beard

and Richard the Lion-heart; they seem half to belong to the realm of fable. We

feel from our very school days as if we could shake hands with a Themistocles

and sit down in the company of a Julius Caesar, but we are awed by the

presence of those tall and silent knights, with their hands folded and their

legs crossed, as we see them reposing in ful armor on the tombs of our

cathedrals.

And yet, however different in all other respects, these men, if they once

lift their steel beaver and unbuckle their rich armor, are wonderfully like

ourselves. Let us read the poetry which they either wrote themselves, or to

which they liked to listen in their castles on the Rhine or under their tents

in Palestine, and we find it is poetry which a Tennyson or a Moore, a Goethe

or a Heine, might have written. Neither Julius Caesar nor Themistocles would

know what was meant by such poetry. It is modern poetry, -- poetry unknown to

the ancient world, -- and who invented it nobody can tell.

It is sometimes called Romantic, but this is a strange misnomer. Neither the

Romans, nor the lineal descendants of the Romans, the Italians, the

Provenšals, the Spaniards, can claim that poetry as their own. It is Teutonic

poetry, -- purely Teutonic in its heart and soul, though its utterance, its

rhyme and meter, its grace and imagery, show the marks of a warmer clime. It

is called sentimental poetry, the poetry of the heart rather than of the head,

the picture of the inward rather than of the outward world. It is subjective,

as distinguished from objective poetry, as the German critics, in their

scholastic language, are fond of expressing it. It is Gothic, as contrasted

with classical poetry.

The one, it is said, sublimizes nature, the other

bodies forth spirit; the one deifies the human, the other humanizes the

divine; the one is ethnic, the other Christian. But all these are but names,

and their true meaning must be discovered in the works of art themselves, and

in the history of the times which produced the artists, the poets, and their

ideals. We shall perceive the difference between these two hemispheres of the

Beautiful better if we think of Homer's "Helena" and Dante's "Beatrice," if we

look at the "Venus of Milo" and a "Madonna" of Francia, than in reading the

profoundest systems of aesthetics.

A volume of German poetry is called "Des Minnesangs FrŘhling," -- "the Spring of the Songs of Love"; and it contains a collection of the poems of twenty German poets, all of whom lived during the period of the Crusades, under the Hohenstaufen Emperors, from about 1170 to 1230. This period may well be called the spring of German poetry, though the summer that followed was but of short duration, and the autumn was cheated of the rich harvest which the spring had promised. Tieck, one of the first who gathered the flowers of that forgotten spring, described it in glowing language.

"At that time," he says, "believers sang of faith, lovers of love, knights described knightly actions and battles; and loving, believing knights were their chief audience. The spring, beauty, gayety, were objects that could never tire: great duels and deeds of arms carried away every hearer, the more surely, the stronger they were painted; and as the pillars and dome encircle the flock, so did religion, as the highest, encircle poetry and reality; and every heart, in equal love, humbled itself before her."

Carlyle, too, has listened with delight to those merry songs of spring. "Then truly," he says, "was the time of singing come; for princes and prelates, emperors and squires, the wise and the simple, men, women, and children, all sang and rhymed, or delighted in hearing it done. It was a universal noise of song, as if the spring of manhood had arrived, and warblings from every spray -- not indeed without infinite twitterings also, which, except their gladness, had no music -- were bidding it welcome."

And yet it was not all gladness; and it is strange that Carlyle, who has so

keen an ear for the silent melancholy of the human heart, should not have

heard that tone of sorrow and fateful boding which breaks, like a suppressed

sigh, through the free and light music of that Swabian era. The brightest sky

of spring is not without its clouds in Germany, and the German heart is never

happy without some sadness. Whether we listen to a short ditty, or to the epic

ballads of the "Nibelunge," or to Wolfram's grand poems of the "Parcival" and

the "Holy Grail," it is the same everywhere. There is always a mingling of

light and shade, -- in joy a fear of sorrow, in sorrow a ray of hope, and

throughout the whole, a silent wondering at this strange world.

Here is a specimen of an anonymous poem; and anonymous poetry is an invention

peculiarly Teutonic. It was written before the twelvth century; its languageis

strangely simple, and sometimes uncouth. But there is truth in it; and it is

truth after all, and not fiction, that is the secret of all poetry: --

It has pained me in the heart,

Full many a time,

That I yearned after that

Which I may not have,

Nor ever shall win.

It is very grievous.

I do not mean gold or silver;

It is more like a human heart.I trained me a falcon,

More than a year.

When I had tamed him,

As I would have him,

And had well tied his feathers

With golden chains,

He soared up very high,

And flew into other lands.I saw the falcon since,

Flying happily;

He carried on his foot

Silken straps,

And his plumage was

All red of gold...

May God send them together,

Who would fain be loved.

The keynote of the whole poem of the "Nibelunge," such as it was written down at the end of the twelvth, or the beginning of the thirteenth century, is "Sorrow after Joy." This is the fatal spell against which all the heroes are fighting, and fighting in vain. And as Hagen dashes the Chaplain into the waves, in order to belie the prophecy of the Mermaids, but the Chaplain rises, and hagen rushes headlong into destruction, so Chriemhilt is bargaining and playing with the same inevitable fate, cautiously guarding her young heart against the happiness of love, that she may escape the sorrows of a broken heart. She, too, has been dreaming "of a wild young falcon that she trained for many a day, till two fierce eagles tore it." And she rushes to her mother Ute, that she may read the dream for her; and her mother tells her what it means. And then the coy maiden answers: --

"No more, no more, dear mother, say,

From many a woman's fortune this truth is clear as day,

That falsely smiling Pleasure with Pain requites us ever.

I from both will keep me, and thus will sorrow never."

But Siegfried comes, and Chriemhilt's heart does no longer cast up the bright and the dark days of life. To Siegfried she belongs; for him she lives, and for him, when "two fierce eagles tore him," she dies. A still wilder tragedy lies hidden in the songs of the "Edda," the most ancient fragments of truly Teutonic poetry. Wolfram's poetry is of the same somber cast. He wrote his "Parcival" about the time when the songs of the "Nibelunge" were writen down. The subject was taken by him from a French source. It belonged originally to the British cycle of Arthur and his knights. But Wolfram took the story merely as a skeleton, to which he himself gave a new body and soul. The glory and happiness which this world can give is to him but a shadow, -- the crown for which his hero fights is that of the Holy Grail.

Faith, Love, and Honor are the chief subjects of the so-called Minnesńnger. They are not what we should call erotic poets. Minne means love in the old german language, but it means, originally, not so much passion and desire, as thoughtfulness, reverance, and remembrance. In English Minne would be "Minding," and it is different therefore from the Greek Eros, the Roman Amor, and the French Amour. It is different also from the German Liebe, which means originally desire, not love.

Most of the poems of the "Minnesńnger" are sad rather than joyful, -- joyful in sorrow, sorrowful in joy. The same feelings have so often been repeated by poets in all the modern languages of Europe, that much of what we read in the "Minnesńnger" of the twelvth and thirteenth centuries sounds stale to our ears. Yet there is a simplicity about these old songs, a want of effort, an entire absence of any attempt to please or to surprise; and we listen to them as we listen to a friend who tells us his sufferings in broken and homely words, and whose truthful prose appeals to our heart more strongly than the most elaborate poetry of a Lamartine or a heine. It is extremely difficult to translate these poems from the language in which they were written, the so-called Middle High-German, into Modern German, -- much more so to render them into English. But translation is at the same time the best test of the true poetical value of any poem, and we believe that many of the poems of the Minnesńngers can bear that test. Here is another poem, very much in the style of the one quoted above, but written by a poet whose name is known, -- Dietmar von Eist: --

A lady stood alone,

And gazed across the heath,

And gazed for her love.

She saw a falcon flying.

"Oh happy falcon that thou art,

Thou fliest wherever thou likest,

Thou choosest in the forest

A tree that pleasest thee.

Thus I too had done,

I chose myself a man:

Him my eyes selected.

Beautiful ladies envy me for it.

Alas! why will they not leave me my love?

I did not desire the beloved of any one of them.

Now woe to thee, joy of summer!

The song of birds is gone;

So are the leaves of the lime tree:

Henceforth, my pretty eyes too

Will be over cast.

My love, thou shouldst take leave

Of other ladies;

Yes, my hero, thou shouldst avoid them.

When thou sawest me first,

I seemed to thee in truth

Right lovely made:

I remind thee of it, dear man!"

These poems, simple and homely as they may seem to us, were loved and admired by the people for whom they were written. They were copied and preserved with the greatest care in the albums of kings and queens, and some of them were translated into foreign languages.

One of the most original and thoughtful of the "Minnesńnger" is the old Reinmar. His poems, however, are not easy to read. The following is a specimen of Reinmar's poetry: --

High as the sun stands my heart;

That is because of a lady who can be without change

In her grace, wherever she be.

She makes me free from all sorrow.I have nothing to give her, but my own life,

That belongs to her: the beautiful woman gives me always

Joy, and a high mind,

If I think of it, what she does for me.Well is it for me that I found her so true!

Wherever she dwell, she alone makes every land dear to me;

If she went across the wild sea,

There I should go; I long so much for her.If I had the wisdom of a thousand men, it would be well

That I keep her, whom I should serve:

May she take care right well,

That nothing sad may ever befall me through her.I was never quite blessed, but through her:

Whatever I wish to her, may she allow it to me!

It was a blessed thing for me

That she, the Beautiful, received me into her grace.

Carlyle, no doubt, is right when he says that, among all this warbling of love, there are infinite twitterings which, except their gladness, have little to charm us. Yet we like to read them as part of the bright history of those bygone days. One poet sings: --

If the whole world was mine,

From the Sea to the Rhine,

I would gladly give it all,

That the Queen of England

Lay in my arms,..

Who was the impertinent German that dared to fall in love with a Queen of England? We do not know. But there can be no doubt that the Queen of England whom he adored was the gay and beautiful Eleanor of Poitou, the Queen of Henry II., who filled the heart of many a Crusader with unholy thoughts. Her daughter, too, Mathilde, who was married to Henry the Lion of saxony, inspired many a poet of those days. Her beauty was celebrated by the Provenšal Troubadours; and at the court of her husband, she encouraged several of her German vassals to follow the example of the french and Norman knights, and sing the love of Tristan and isolt, and the adventures of the knights of Charlemagne...

... much that is noble and heroic in the feelings of the nineteenth century has its hidden roots in the thrirteenth. Gothic architecture and Gothic poetry are the children of the same mother; and if the true but unadorned language of the heart, the aspirations of a real faith, the sorrow and joy of a true love, are still listened to by the nations of Europe; and if what is called the Romantic school is strong enough to hold its ground against the classical taste and its royal patrons, such as Louis XIV., Charles II., and Frederick the Great, -- we owe it to those chivalrous poets who dared for the first time to be what they were, and to say what they felt, and to whom Faith, Love, and Honor were worthy subjects of poetry, though they lacked the sanction of the Periclean and Augustan ages.