(Review follows of "Island" by Aldous Huxley.)

Of all the books set by our readers club, this was the one, that to date I most clearly enjoyed. (Later, I favored Julian Barnes' "Arthur and George" - also reviewed on site - but that is a contrasting kind of book. Neither is a substitute for the other.) The narrative character is a water supply official sent to investigate disruptions in the water supply to towns along the bay of Naples. In town, the reservoir had emptied. A trove was uncovered in the basin.

He sets off on a fresh and sunny morning, climbing the hills, with only his own company. The official has something of the hauteur of a minion of the Emperor's public business. He is searching for some unreliable water works employee. He turns out to be an unpleasant character, who he meets with only his own slender resources to see him thru. One knows that this is not the end of their encounters.

The novel is like a holiday book, in the best sense of being like a holiday to read, rather than being a book you take to recuperate with. The expert's knowledge has been passed down, and in the course of the novel we learn the simple but effective basis of the ancient Roman penchant for colossal structures. Among these are the miles upon miles of more than man-size pipe bores that carry water to dependant settlements without springs.

Climbing down inside, he finds one of the bores has been disrupted. Back in town, he has another set-to, this time with some self-made barrow boy and empire-climber. Another one for a final reckoning. There are earth tremors. No great significance is attached to these. But they emanate from the book's only real character, Vesuvius, who asserts himself eventually quite recklessly. Many must have been sorry they did not take him seriously. Only a few knew enough to read the signs of the extent of his coming out-bursts.

Pliny features as encyclopedic mind, rescuing admiral of the Roman Fleet and himself a victim. (The account of his nephew, Pliny the Younger, is also featured on site here.)

There is a heroine, in keeping with the token characterisation, and an attempted rescue, as the volcanic menace approaches. A few clevernesses of plot sustain the narrative as an adventure. Read the book to find out. It is true that Robert Harris is still more historian than novelist in this work but he carries his learning lightly. There is no heavy back-pack to carry on this literary traveling light. No disparagment is meant by saying it is a light read.

I can't say that his fictions, as alternative modern history, appeal to me as much. Of course, this modern historian is much better informed than this reviewer. But I still am fairly conversant with the Soviet era. So, in Harris' novel "Archangel", I found myself wondering how close was this fictional account to the witness accounts of Stalin's last days and hours. A recent documentary suggested that history still does not really know why Stalin ended, as he did, and who was responsible or irresponsible. The secret state keeps its secrets still.

No doubt Harris indulges some informed guess-work. To be sure, it isnt a sympathetic farewell to a fellow human being bound on our common destination, he sent so many to, prematurely. I can't say I found the basic plot idea compelling. Harris' brother novel to "Archangel" is based on a similar premise. "Fatherland" is not about the threat of a resurgent Stalinism but an alternate history of the Nazis winning world war two.

I dont find this a compelling possibility, which is why I havent read the book. It's been done probably many times, if not by one so learned in the history. A case in point is "The Pelican Brief", about which one critic regretted that the film wasnt brief, too. Philip K Dick re-wrote the war in "The Man In The High Castle." General Rommel was made high commander of North America. But this was from the point of view of the Japanese as amiable orientals, as cautious of their co-victors as of the vanquished.

Richard Lung

2 october 2006.

Armaments, universal debt and planned obsolescence -- those are the three pillars of Western prosperity. If war, waste and moneylenders were abolished, you'd collapse. And while you people are overconsuming the rest of the world sinks more and more deeply into chronic disaster. Ignorance, militarism and breeding, these three -- and the greatest of these is breeding. No hope, not the slightest possibility, of solving the economic problem until that's under control.

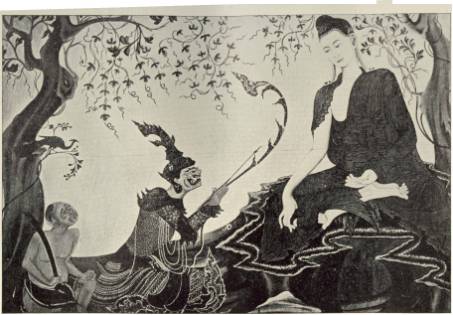

Island ( 1962 ) was the one last novel Aldous Huxley wanted to write. It is a utopia or ideal society, imagined in the wisdom of his last years. This is a more mature work than Brave New World, for which his name is best remembered. The latter is a dystopia rather than a utopia. Destructive criticism, of the obvious faults of society, however cleverly projected, is easier than creating a realistic and interesting alternative.

In point of fact, there isnt much of a plot to Island. It is a vehicle for Huxley's pet ideas about human betterment, to be recognised with affection by those who appreciate his company. That does not mean to say he has forgotten to set the scene. The reader is soaked in an exotic landscape and culture.

An obscure south asian island has luckily escaped colonial exploitation and indoctrination. The best of ancient oriental religous philosophy survives to meet the best of modern scientific progress, in the two founding figures of a humane social experiment that works -- so the author would have us believe.

But the modern world finds that these blessed folk have oil to plunder. The narrative character is a hack journalist, being bribed as a spy to serve his boss's portfolio of interests. He gate-crashes the island, in a ship-wreck. As he recovers, he is given a conducted tour of the utopia.

One of the survivor's first encounters is with a talking myrnah bird:

'Attention!' It repeats. The old rajah freed a thousand of these instructors

about the island.

Attention to what?

One finds out the answer is: Attention to attention. What else?

'Here and now, boys, here and now,' the bird goes on. The idea is that one

lives for the moment, meaning that one live in the eternal present.

Will, the castaway is carried on a stretcher to the doctor, for attention.

From his moving bed Will Farnaby looked up through the green darkness as though from the floor of a living sea. Far overhead, near the surface, there was a rustling among the leaves, a noise of monkeys. And now it was a dozen hornbills hopping, like the figments of a disordered imagination, through a cloud of orchids.

The journalist's only baggage is a bad conscience. He deserted the woman, who loved him, for another he craved. The latter, of course, got rid of him when it served her turn. The regreted triumph of lust over love also marked a relationship that started off Ape and Essence. This dystopia was Huxley at his most resigned. Written at the end of world war two, it seemed that scientific progress was matched by moral regress. What then more natural for the author to take human debasement to its logical conclusion?

Ape and Essence was one of science fiction's early post-nuclear war scenarios, of which thousands were to be written. Human remnants, on west coast America, are still plundering their fellows. But those best preserved are in the mausoleums of the new rich, where they turn out to have been embalmed to a living likeness, and in all their worldly livery.

However, the journalist, on Island, is given psychological, as well

as physical healing. Describing a place he knows, as a peaceful and happy

memory, takes him back there in his imagination. And putting the patient in a

light trance removes distraction of the mind from healing the body.

It is all rather over-shadowed by the impending fate of the island. A hundred

years' humanitarian work is about to be wrecked over-night by ruthless greed.

Inside help for the coup comes from a gushing 'spiritualist', regal,

self-regarding and over-bearing, together with her son, Murugan's adolescent

power drive:

"One of the first things I'll do is to build a big insecticide plant." Murugan laughed and winked an eye. "If you can make insecticides," he said, "you can make nerve gas."

War, famine and disease are the usual results of over-population, tho they cannot be said to have controled it. Famine could be averted by breeding improved food-stuffs. But the usual result is an increased birth-rate, unless there is birth-control. Huxley's island of 'Pala' happens to inherit a Mahayana and Tantrik strain of Buddhism. People accept that 'begetting is merely postponed assassination', and use traditional means of contraception, known since the stone age.

The esoteric practices of 'the yoga of love' are taught to the common people. Sexual union is used as a means of transcending one-self with a partner, rather than mere self-gratification of bodily appetite. And, in general, sensation is not denied for some nirvana, but as a means of transcending one's narrow identification of the self with one's bodily nature.

Much evident in the novel is Huxley's famous pre-occupation with mind-expanding drugs to escape the prison of ego. He cautions they are not suitable for people with certain physical and mental disabilities, such as a liver condition or schizophrenia. Huxley might have added that all prescriptions may be more or less disallowed because of side effects. He also wrote essays on his drug trips: The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell.

Much to the scorn of the modern consumer addict, Murugan, the islanders are happy without 'economic growth'. Pretending to be a virtuous school-boy learning Elementary Ecology, he secretes a mail order catalog in his desk. Elsewhere, in the novel, comes the comment that compassion and intelligence toward nature make ecology applied Buddhism.

Pala is neither capitalist nor state socialist. It relies on de-centralisation and co-operatives in agriculture, industry and finance. Instead of over-specialisation to maximise production, job satisfaction is sought by a part-time system of sampling different jobs. Since Huxley's day, more flexible working arrangements only gradually became accepted.

Ends and Means and Brave New World Revisited are among his main studies on social reform. The Perennial Philosophy perhaps is his main look at personal improvement, a problem which death itself may not put an end to. But the two approaches are really part of each other. In Island, there is no artificial separation, of personal and social welfare, for the convenience of exposition.

Huxley was much taken with Sheldon's theory of personality based on three body

types. No doubt he was influenced by being an obvious 'ectomorph'. Later tests

have discredited the theory. Huxley is on safer ground with the

introvert-extravert personality range, associated with C G Jung, and so

successful as to enter into the popular consciousness of relationships.

In Island, a woman describes her mother as being like 'a permanent invasion of her privacy', because she is so exhuberant in her extraversion. The daughter admits to being like her introvert father, regarded by his wife as lacking common feelings, because he is so withdrawn.

Modern industrial society aggravates mental disturbances by forcing incompatible personalities to live together in 'the telephone box' of the nuclear family. In 'Pala', they have informal extended families, Mutual Adoption Clubs, with more than one 'mother' or 'father'. When members of the biological family are getting too much on each other's nerves, they can stay away from home, for a while.

There is no maternal clinging. If parents and children dont get on, they dont force themselves upon each other's company. It is considered natural to go one's own way.

Children are acclimatised to other children of incompatible physiology and

temperament. All the nervous, tense introverted children are put together. A

few boisterous kids are introduced to their group, till they learn the right to

exist of people different from themselves. For squabblesome small children,

different personality types are likened to different kinds of animals,

cat-people, sheep-people, guinea-pig-people etc, so even they can understand

contributing causes to their conflicts.

As a celebrity once said about her pets: I keep cats and dogs together. It

broadens their minds.

If Western families are as socially claustrophobic as telephone booths, the schools also are like boxes. Huxley describes westerners as 'sitting addicts' who have lost the right balance in their lives between mental and manual labor. Huxley's characters argue: Not 'back to good old child labor' but rather 'forward from bad new child idleness'.

Practical work and challenging recreations also work off aggression, which judging by contemporary schooling, there is much need of. Huxley was in many ways a prophet.

Late on in the story, we join an inspection of a Palanese school, taking a cross-section of its lessons, that give a particular flavor to Huxley's thoughts on education, which I wont attempt to convey. This review doesnt do justice to the variety and subtlety in his novel of ideas.

He recognises that emotionally damaged individuals, in power, can cause, in their turn, incalculable damage of all kinds, mental, physical, emotional, social, economic... The EH, as he calls it, the Essential Horror of life has no single solution, but must be tackled on many fronts. The specialist sciences, especially the biological and psychological sciences have their part to play. They should be grounded in an accumulated practical wisdom such as some types of Buddhism, which are scientific in the sense of stressing immediate experience and deploring unverifiable dogmas that dictators work on people with.

Schumacher's Small Is Beautiful satirises the naive assumptions of western economics. He demonstrates that other moral imperatives can be used to supply an economics, in which human beings matter, sketching out a 'Buddhist economics' as one possible instance.

For Huxley, the EH haunts both the personal life and the mass spectacle. A malignant disease like cancer can destroy not only the body but radiant goodness of character. One of the Palanese children's lessons is that pain is a warning that must be heeded, in the attempt to find a cure. But there are also spiritual techniques to lessen the pain once its message has been received and acted on.

Huxley was much ahead of his time. He was cosmopolitan when the England he left, for futuristic California, was still parochial. Now, you dont have to go far in England to find local societies that are Huxleyan in their oriental pre-occupations.

Richard Lung

The first half of this first novel is a good character-driven plot. I didnt realise that it was a plot, taking me by surprise, as authors like to do. All credit to the author, he was only reproducing an effect of long experience. You look back on your life and see it in ways you hadnt realised.

The narrative character Amir is pretty mean but redeems himself thru an honest retrospective, and does eventually atone for his childhood misdeeds, as he had to, to live with himself, or indeed with the readers' patience.

Amir is a child with a child servant and play-mate or rather play-servant. Hassan, the servant, who is better than his master has been done famously before, in comic, heroic or tragic versions. But this account in no way suffers from comparisons. The faithful servant is faithfully rendered. The draw-back of such master-servant relationships, in a post-feudal age, is that the servant seems misguided - a chump, to put it plainly.

But Hassan, in his simplicity, never loses his dignity. One only feels about him, that it is a pity such good service were not put to better use. But one of our readers' club said Hassan gave "unconditional love."

The father of Hassan is Ali and the father of Amir is Baba. That goes together to remind of Ali Baba and the forty thieves. As it happens, theft, Baba says, is the one deplorable sin, by which all the others can be described. I didnt know that Muslims had caste differences. Apparently, Hassan was of a lower caste Hazara. The novel says there were killings of them by the Taliban. There was also a Muslim religious divide, in Afghanistan, between Shi'a and Sunni, which we've heard so much of in Iraq of late.

These divides prevent Amir from so much as calling Hassan his friend, tho he uses him as such, enough to attract unwelcome attention from the prejudiced. Of course, there are obvious parallels to such racial and religious discrimination and its obduracy in the West.

Less than half way thru the story, Baba and his son have fled from the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. I wondered if the novel was going to descend into a colourless account of the American consumer society. Well, they are in it at the bargain basement level of the car-boot sales. Baba the refugee is reduced from a bear like tower of strength for his community to a chain-smoking pump attendant wasting away on cancer.

But in this reduction the bear reduces to a human size that his son can at

last relate to, in a way he craved, as a boy. In his last days, the father

becomes the helper and companion to his son, that he was so renowned for being

to so many others of his countrymen. It is the other touching relationship of

the novel.

It does not matter where Hassan and Baba come from, they win the reader's

regard as real people might. This is welcome relief from the characterless

stream-of-consciousness indulgences of the modern novel.

Like his narrrative character, Amir, the author doesnt seem to know much about women, tho. His wife only comes to life when sparks fly in conflicts with her father. He is an exiled bureaucrat, who never doubts his worth will at last be rewarded by recall to his country's government. His moral mediocrity is a perfect foil for the heroic characters. He is also a well-observed type, tho with a less prominent role in the story.

I only really reviewed this novel because of the characterisation. The return to Afghanistan on a rescue mission didnt have the lived-in feeling of the childhood story. Amir is taken for a tourist. When his privileged early back-ground is guessed by his guide, he concludes: You were always a tourist. You just didnt know it.

The novel treats the Taliban as a culminating affliction of Afghanistan.

Tho, they dont have a monopoly on arrogant young men with arms. Many people

already deplore their human rights violations, anyway. We never really get an

insight into their mentality, which is what a novel is supposed to give.

A BBC documentary in Kabul gave more of a feel for things. But that, too, seems

hopelessly out of date, judging by a report of the once again degenerating

order. A long article, Death Trap, in The Sunday Times, 9 july 2006, by

Christina Lamb, supplied much more about the dire plight of the people, and any

attempts to help them, than conveyed in half a novel.

The novel itself rather degenerates into a vendetta, which threatens to become a saga. Again, the author's sensitivity to children is apparent in the son of Hassan. But the cruelty of events confines the novel to adults' book-shelves. If this plot heads for Hollywood, it is liable to come out as yet another revenge movie, that may not make audiences much the wiser.

Tho the plot turns into a melodrama with a mad and vindictive villain, that

is not to say the author believes in revenge. Hassan is recalled as having said

that you must not harm others and that even bad people may become good.

We all may hope to become better people.

The novel ends with a glimmer of hope as Amir, about to run the kite, quotes Hassan to his withdrawn son: For you, a thousand times.

Richard Lung

20 july 2006.