(Review of A S Byatt's "Possession" follows.)

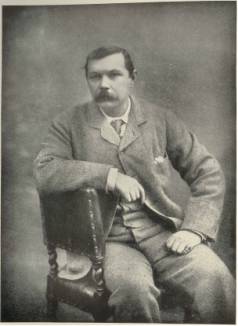

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

This has been the most "engrossing" read, to quote a truthful blurb, that our Readers Club has provided me. In a way, it is an exception that proves the rule. It is almost as if Julian Barnes has picked up some of the dust from the golden age of English literature, from which he has borrowed this true story, to be given imaginative life.

For the eponymous Arthur is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. George Edalji is from a family of one of the early Parsee Indian settlers in Britain. His thoughts are entered-into with almost as fascinating, because thoughtful, detail as are Arthur's. These are two people with minds that are worth inhabiting, which says a lot for the intelligence of the author.

Both Arthur and George have the snobberies, long since discredited, of their Age. (George's minister father patiently tries to lead him out of them.) But we do not dislike George or Arthur, at least I didnt. The finer qualities of they and their families are made evident, without the moralising, once called Victorian. George is patient and tolerant and seeks to reach a just estimate of those, he might be forgiven for giving up. Both men see deficiencies in the other but also make allowances for deficiencies in their own judgment, to arrive at more balanced character assessments.

Arthur becomes the man of chivalry, he always wanted to be. It redeems wholly the archaic pre-occupations with his family's heraldic status, like another Sir Walter Scott, whose feudal pretensions even the Victorian Macaulay derided. Sir Arthur, the sort of social climber, who didnt seem to think a knighthood good enough for him, till the Ma'am told him otherwise, doesnt take a moment to put his sense of honor before being agreeable to the Establishment.

The wrongful imprisonment of an innocent man, George, leaves the Home Office to do its best not to admit the wrong, tho that compromises a man's good name and reputation and livelihood. Arthur rages at their incompetance and inconsequence. It makes the reader give a silent cheer.

Two disappointments of the book are not the fault of the author. Those

guilty of the "Outrages" against animals, in the area of minister Edalji's

parish, are not brought to justice, because of the back-ward and prejudiced

policing. There was also malicious misrepresentation. Tho, Doyle does seem to

identify the worst offenders.

I guess why the police inspectors, in the 1930s and 1940s Sherlock Holmes

films with Basil Rathbone, are ill-educated dupes. It may be a left-over

perception of certain inexpert constabularies of the nineteenth century, such

as graced the Edalji case. A poison pen letter-writer in the area was

eventually convicted.

The second disappointment was the verdict, also inconclusive, on Doyle's cause of Spiritualism or Spiritism, as he prefered to call it. Doyle did write a fantasy on this (one of his Professor Challenger novels), and I felt that his views there had something of wishful thinking in them. To his credit, Barnes leaves the door open on the subject, without feeling able to come up with any reason to believe in spirits of the dead communicating with the living. Doyle's favorite medium comes over as rather unsatisfactory.

Ive heard the contemporary medium Stephen Fry, on one of the digital freeview channels, and I dont know how he knows about details from the lives of former relatives of members of the audience. Sceptics put forward the usual explanations of fraud or deception or unintentional fraud from sub-conscious information cues. In his novel, Barnes mentioned that other old favorite explanation: statistical guesswork - from an audience as large as the Albert Hall's.

Barnes doesnt go into Doyle's gullibility about "the fairies in the garden" that two girls crudely mocked-up from fotos of cuttings. It's well outside the period of the story. He does mention that his father was a rather good painter of fairies.

Doyle's limitations dont matter so much. Everyone has limitations. Much more to the point is the comprehensive energy and ability from a youthful maturity. I admit to envying how well such people make their way in life. That's to say nothing of his achievements as a "sportesmann". And he knew how to live from his accomplishments. He found a micro-climate "Switzerland in England" to suit his wife with TB, and built a fine house there amongst hills and trees.

Barnes is never superior to his characters but is perfectly in sympathy with their out-looks, so that we seem to have the privilege of being them. They are humans not idols. Doyle's Affair is particularly convincing in the way it happens to him. He rigidly adheres to his code of honor. There is an ultimate irony to this. Meanwhile, Barnes intimates the various points of view, even of the bachelor secretary, considering how husbands get bored with their wives.

It becomes clear that Doyle's eventual second wife never got bored with

her older husband but patted her hair, like a girl, and ran to meet him.

It's curious to think back to her introduction to a posthumous collection of

the historical novels, where she goes into the immense amount of research he

did. Obviously, she had not given up on his belief that they were his real

work as a novelist.

I believe there is one minor incident, in which the author slips. That is the case of the mono-rail, the affluent Doyle has installed in the garden, as the transport of the future, as H G Wells has persuaded him. But Doyle's son makes infuriating remarks about it being too small and slow.

One feels that Barnes is inviting us to laugh at one of those ludicrously inaccurate prophecies about another invention that never realised its hopes. Barnes does not disabuse the reader of the idea that the mono-rail was just a clattering curiosity, much as the ancient Chinese regarded some genius' prior invention of the steam engine as a toy.

I believe the modern mono-rail uses magnetic repulsion of vehicle from rail, to achieve frictionless super speeds. Yes, I grant you, it has not come into general use and probably never will. And future traffic may be based not on mono-rails but zero-rails!

Yet, the gyroscope, that can keep a vehicle balanced on a mono-rail, is in

standard use, as a ship's stabilizer, as an air-craft's auto-pilot, a

rocket's guidance system, and no doubt comparable uses, if I were to pretend

to be more knowledgable from checking them.

I suspect also that gyroscopic propulsion may one day be inspired by

atmospheric electrical vortexes.

The real significance of the mono-rail mention may be that Wells and Doyle were much nearer the mark than the author is aware. And that, whereas they were forward-looking and scientificly literate, modern English literature may be neither.

That incidental scientific gripe should not detract from the excellence of

this novel. As a psychology of characters, most novels dont remotely

challenge its depth. As an appreciation of how the law should work, as well

as why it doesnt, this novel is a good mental discipline, as well as a good

and true to life story.

As Ive said, the most interesting Readers Club book Ive read, to date.

October 2006.

An impressive amount of ability and hard work has gone into this novel of some 500 large pages in close print. This suggests a deal of commitment to what it stands for. Romance, as the sub-title says? Well yes, but not, I think, 'the romance of religion', or rather, not in the other-worldly sense G K Chesterton meant by the phrase.

Speaking for myself, I found Byatt's luxurious style a welcome contrast to the mundane novels, Ive come across from her famous sister, Margaret Drabble. But I admire Drabble's critical mind in its plain prose. She is a distinguished literary critic. But more than that, she was willing to contest a neglected cause, that of greater equality of income.

And I bring this in, because, it seems to me, Byatt's Possession is a prodigious work to no very great purpose. It is as tho the sisters still had much to learn from each other. Possession and her other writings may have possessed themselves of the glittering prizes. But book awards tend to be academic judgments of 'literature' more than anything else. Rewards for ideals, or what have you, are cleaved into the odd peace prize. This often goes to politicians, whose job peace is, it should go without saying.

Perhaps the secret of Possession is that it has no purpose. The

novel is enjoyed for its own sake. ( One might say as much for

possessiveness. ) Byatt's artistic scenes clutter the imagination with

curios. One dwells, one luxuriates, in their gothic atmospheres. Bibliophiles

are especially pandered to, with a succession of libraries, voluminous, state

of the art, specialist, and discoveries of literary treasure troves.

Tho, the fifty pages of illicit love letters, in best Victorian style of

pompous circumlocutions and affected emphases, were a considerable brake on

this reader's progress.

Apparently, Byatt studied her task before producing accomplished passages of blank verse and more feminine lyrics. They interrupt her novel, for some readers, but provide clues that two nineteenth century poets, Randolph Henry Ash and Cristabel La Motte were together on a surreptitious holiday.

Fusty book shelves are well off-set by provincial wildernesses of England and France. Cristabel comes from French immigrants and we are reminded of the artistic Italian immigrants, the Rossettis. Cristabel's companion in love, Blanche Glover is a painter. And one of the pre-Raphaelite's names is put to an Ash portrait. You get the picture.

The plot is driven by twentieth century academic rivalry over discovering the unsuspected relation between Ash and La Motte. Two American researchers are in on the hunt. They are powerfully drawn and their wealth over-whelming. They are also the main comic relief, in a context that takes itself so seriously, namely romanticism.

The English characters may be irritating, pitiable, pathetic or deplorable but are not generally laughed at. It is as if they are the true heirs, however debased, of the romantic agony.

It seems true that Byron manages to escape the spiritual malaise named after him, in his self-mocking Don Juan. Early verses express a determination his epic should go on indefinitely. He eventually abandons it on the point of another secret affair, perhaps bored off his head by the prospect of setting himself a further bout of sexual propaganda.

Anyway, Possession is a pastiche of the English romantic movement; its family and cultural circles. The radicals are mentioned, in the name of Mary Wollstonecraft and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

The married poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning are drawn on. Robert appeared to have a grudge against the apparent powers of spiritualist D D Home, whom he versifies or vilifies as Dr Sludge. This was not the opinion of Elizabeth or of other contemporary witnesses.

Byatt has her fictional poet, Ash, write a cynical revelation of a

spiritualist dubbed Sybilla Silt. It is done with some verve.

Sybilla also gets her say, as having seen Ash's luridly angry aura. However,

this can be viewed as sensitivity to a natural phenomenum. While Sybilla's

integrity is restored, the plot does not depend on any supernatural agencies

at work. God Himself is like the locked-up church in Cristabel's graveyard:

no longer in business. Another house of God is converted to a tourist

reception centre.

Ash is characterised as a student of the new sciences of his time, such as geology and micro-biology. A secular religion depends on some idea of scientific advancement or progress. But the modern English literature academics betray no awareness of the burgeoning of scientific ideas. That is perhaps a weakness. Tho, most of us lack technological foresight, so not much can be made of the fact that the novel is set firmly in the era of type-writers and the photo-copier is regarded as a great democratic invention.

Rather than science, the novelist's concern is with better matched

relationships. As soon as one of the nineteenth century characters finds

herself 'superfluous', by coincidence, a twentieth century character

expresses the same opinion of herself.

A psychologically deep folk tale, by La Motte, The Glass Coffin has

a hidden parallel in the lodgings of the unemployed academic and his

'superfluous' bread-winner. The land-lady wont let them out of their

underground room, into her garden.

In the end, this hero of our time does find his way out there. It is a

symbolic liberation, in which the first ideas for poems of his own come to

him. The incident is nicely under-stated but may give a vital clue to the

novel's secular religion. That is, value is placed on one's creativity as a

personal contribution to the Creation.

But it should be said, he has just been offered employment. So, creativity

had to wait on practicality. As in J M Coetzee's Disgrace, there is

an unconcealed disillusion with English literature studies, as pretentious

and unfruitful.

This is as well as the usual worldly belief in finding a suitable partner

and continuing the line of procreation, which is what the cleverly wrought

plot is about. The sex drive generally doesnt permit the young not to take it

seriously.

The novel also caters for gourmets, tho a less sympathetic character is given

the job, with special culinary tools, of demolishing the shell and picking

clean the inner flesh of a sea spider.

We are in an indulgent exploration of the sensory world, from the gross to the refined, rather than a speculation about other worlds.

Richard Lung.