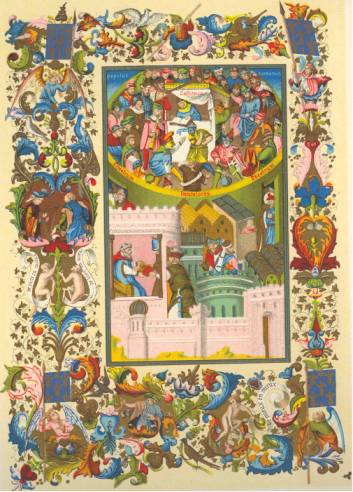

Page from the fifteenth century Comedies of Terence,

in the library of the Arsenal, Paris.

Enlargement ( 291 kb ).

Quite early in his play-writing career, Alan Ayckbourn became the world's most performed playwright. There was a decade's resistance from the literati, refusing to publish his work because it was 'not literature'. He has over-come such hiccups. Recently, a knighthood officially confirmed the long-standing popularity. Currently, he is about to publish another book.

He has arrived -- from a journey that began in his boyhood, when it was possible to see thirteen films a week, in town. And he did -- usually twice over. ( His mother didnt mind this, because she knew where he was all the time. ) When you are that age, you cannot judge between good and bad. You may prefer the worse films. The good ones tend to have more talk in them.

At school, he was lucky enough to have a teacher who was a theatre nut,

taking them to see plays. Ayckbourn remarks on how the class-room teaching of

Shakespeare can put children off. But his teacher used a tacky model theatre,

in which he moved figures on and off stage, while the children read the parts,

so they got a real sense of what was going on.

It was Ayckbourn's first lesson in the importance of how that space on the

stage is used.

Not surprisingly, the young cinema addict wanted to be an actor. He left school frustrating his teachers' ambitions for him to go to university. Instead, he joined a theatrical company directed by Donald Wolfitt.

Looking back, he does not know why he went into theatre rather than films. (

It may have had something to do with school not yet recognising cinema as a

curriculum subject. But that is only this writer's guess. ) Tho films started

off Ayckbourn, he has had very little to do with them. Little has been made of

his plays by the movie industry.

He wryly admits that the only time he wrote anything for television coincided

with a hiatus that broadcasters used to describe as: due to circumstances

beyond our control.

A theatrical apprentice often has to stand in for all the back-stage jobs, like lights and props, as well as the on-stage job. This would stand him in good stead for the further unforseen job of writing plays. Altho he wouldnt remember the exact details of his days when he worked on the lights, he would recall enough to know how to create his effects.

Stephen Joseph pioneered the Theatre In The Round, which is famously named after him. Its first of three Scarborough locations was in the hall above the public library, which the chief librarian offered Joseph. In those days, the idea of an audience surrounding the actors was not approved in theatrical circles. Tho, it is now common enough, at least, for stages to be built forward into the audience on three sides.

Joseph didnt just have radical ideas in audience involvement, at a time when theatres were closing down from the impact of the cinema and television. He also believed that a theatre company should write its own plays.

Typically, plays were taken from outside without the author's involvement. The author would variously react to the ensuing production with horror, bewilderment or gratitude, and sometimes all three.

Joseph believed in uniting writing and acting into a single process. That is why Ayckbourn follows the tradition of those who say they are playwrights not writers. He does not merely write for the theatre, he directs every stage of production, of which the writing is just one part. He compares his role to a conductor of an orchestra, not a commander.

Being a playwright is not for those who want total control of their work.

The novel is more suited for that. The writer as control freak is the wrong

person for a theatrical production, which is a collaberation of dramatic

skills.

( Perhaps it compares to science, in its 'adaptation' of theory to practise.

)

When Joseph started Ayckbourn on plays, the latter's motivation was to write incredibly good parts for himself. Like Shakespeare, he started as an actor. After eight years or so, he began to realise that he wasnt the out-standing performer he had hoped to be. So, Ayckbourn says, he sacked himself as an actor, and found better ones for his plays.

It wasnt that he was a bad actor. He was good enough. But that wasnt enough.

How did he know?

Gradually, an actor such as himself finds out his limitations compared with

other actors. It can take some time, as it took Ayckbourn. The luckiest, who

havent got what it takes, find out after only a few years and can move on. Then

again, some actors say they only came into their own by the time they were

forty.

What is it that makes a great actor?

In company, some personalities 'hold the stage' when they are off-stage. Maybe,

as soon as they appear before an audience, they go 'blup'. ( This reminds one

of a Yorkshire pudding, made without skill in the traditional recipe. ) Others

may become totally dull as soon as they get back in the dressing room: they go

'blup'. But, on stage, they just seem to light up. It isnt necessarily beauty

that they possess. One could call it charisma, as Ayckbourn does. That is to

say it is the mystery of a divine gift.

Much the same may be said of writing plays. People sometimes ask Alan

Ayckbourn: Where do you get your ideas?

He doesnt know. He has written sixty two plays, to date. And he can never be

sure whether his latest play is his last. He would certainly miss the

inspiration. And if he did know where his ideas came from, he adds, he wouldnt

tell you!

The playwright first gained his reputation as a writer of comedies. But the public soon became aware his plays never seemed to have happy marriages. He no longer classifies his works as comedies or tragedies. He just calls them plays.

A transition, in his early comedies, was marked by a woman of mistaken

intentions. While a party is going on, she is in the kitchen quietly trying to

do away with herself. A couple, coming in, rightly perceive, but in the most

superficial way, that she needs help. So, they mend the ceiling fitting, when

she fails to hang herself on it. And so on.

This is hardly a comic subject, Ayckbourn concedes. But it foreshadows his

out-look on a world where comedy and tragedy are as intimate as light and

shade.

He was surprised to find his insight anticipated by the post-Shakespearian

playwright John Ford, while treating themes of incest and murder.

The Theatre In The Round doesnt often do classical plays, tho. They dont have

the resources.

Besides light and shade, Ayckbourn further compares play-writing to painting. You know those old masters, with foreground figures in the most richly textured and ornamented dress. Perspective is shown by the scene becoming more blurred, until a back-ground figure is described by a few simple strokes.

Plays also have a perspective on character. The walk-on part, such as a post-man should likewise be scripted with the utmost economy. That doesnt mean the part is unimportant. Never tell an actor that, or he will walk out on you. But the writer wouldnt want the walk-on actor to take a couple of weeks to build up an elaborate study, any more than the writer would interrupt the story by having the post-man launching into a long speech about himself. The audience would wonder what this was all about. The playwright does not want to confuse people, who are there to be put in the picture.

Sometimes a playwright's characters do take over. But this creativity has to

be kept in check, if it is a red herring. Superfluous passages should be cut

before being shown to the actor, who will want to run away with all those

lovely lines. Otherwise, it will be difficult to withdraw the verbiage later.

Chekov knew how to get away with this but not everyone has his tact all the

time. An actress was reading one of his parts, when he realised that her

performance had summed-up everything in the first sentence. He congratulated

her and put a line thru the rest of the passage.

Still more economy is possible. Characters may be alluded-to, and created in the audience's mind without them ever coming on stage. A couple, who are at the party in the next room, are innocently talked about. Tho a few laughs, from next door, are all we hear from them, we are able to form our own impression of them: they are a horrible couple.

In general, the playwright doesnt use more actors than are needed for the story. If he did, the actors would wonder what they were doing here. To the same purpose, Ayckbourn adheres to Aristotle's classic doctrine of the unities of space and time in a play. Only as many scenes are used as are necessary to the story.

It is seldom possible for the action of a play to take place wholly in real time, or for as little as two hours. A two-hour performance, also the length of time portrayed on stage, invests every action with a heavy significance, down to lifting each spoon of sugar into a cup.

Moreover, cinema and even television can beat theatre hollow, in the staging

of a spectacle. In the nineteenth century, theatre tried to do that. But it's

not worth it now. The one thing that the stage is really good at is the

portrayal of the human.

Generally, a play follows the development of character, which implies that the

acts will have to cover several periods of time. Sometimes, the characters dont

learn anything. And that is the point of the play: that they never learn. But

that is really only the exception that proves the rule. A play is like a

journey, in which a character gets from X to Y. If your character is the same

at the end, as he was at the beginning, then your play hasnt really got

anywhere.

For a brief while, Ayckbourn was a university tutor. He found that students

would come to him with good work, which they had no idea of how to finish.

( The main subject of this web site, Dorothy Cowlin confirmed the truth of

this. Her first two attempts at novels were started without a plan, more in

hope of getting somewhere than knowing where she was going. She couldnt finish

them and it was a great waste of time. )

Ayckbourn likes to have the shape of a play in mind first.

The playwright was approached by two veteran writers of tv comedies. They said they were tired of writing for television and would he advise them how to write for the theatre. Reading a proposed script, he found they were still turning out a stream of gags. He thought this would exhaust the audience in minutes.

In Oscar Wilde's plays, everyone is always saying witty things to each other

and no-one ever laughs. Ayckbourn says one of his funniest lines was: 'No.' For

him, comedy comes out of the characters' inter-action.

Ayckbourn is less concerned that the audience should find the characters

amusing than come to see into their natures. Humor does not depend on the

dialog.

The play's construction has priority. The last thing Ayckbourn concerns

himself with in a new play is the dialog. He knows dialog is his forte. He

doesnt do scripts, he does dialog. His style is not literary, if avoiding bad

grammar, like ending a sentence with a preposition. He writes as people talk.

It expresses their character. A play that stops there is purely a radio play.

That's fine in itself but doesnt use the full range of expression on view in a

theatre.

Not to consider the visual impact of one's play is simply to leave the job to

the director.

He is a great believer in filling in the spaces between the words. Merely asking an actress to pause in a speech can attract attention to the meaning. One should not under-estimate the many ways actors and actresses have, their whole body language, other than merely speaking, to convey the spirit of a part.

An actor has to be both subjective and objective in his or her part. Actors are not acting alone but reacting to each other. In rehearsals, the company will decide where they want the audience's attention to be at any one moment. There will always be someone who is looking in the wrong place but, mostly, the effect is achieved.

Children are the most testing audiences for having their attention held.

Adults may give a slow play fifteen minutes or so, to warm up. It takes kids

about three seconds to decide: 'Boring!' and start talking among themselves.

American televisors decided that children's maximum attention spanned eleven

seconds. The changes of camera scene were tailored to that. Obviously, theatre

cannot do that. You are stuck with the current set. Film technique may not

learn from theatre but Ayckbourn says he learns from films.

One means of directing attention was to have the stage action followed by someone carrying a video camera. Conveying a stranger's sense of detachment, one lead character moves thru two worlds. One is the real world of her depressing family. Her imagination compensates her with a happy family, that is in every way delightful.

A woman may think she can be what she likes but it will take its toll of her

system, till she finds out that she cannot, to be greeted by the response:

Whoever thought you could?

In the schizophrenic play, the fantasist starts to confuse her two sets. The

characters of her real and imaginary life begin to mingle on stage. Ayckbourn

could see the audience stirring, wondering what was happening here. As a rule,

he would avoid this incomprehension. Here, it reflected the fantasist's losing

her own sense of the difference between the real and the imaginary.

Like a carnival or burlesque, the mounting chaos at last explodes. As a

super-nova leaves a black hole at its core, so the fantasist's mind shuts down

into catatonia.

Basically, Ayckbourn's play-writing rule, that character must develop, is

qualified with a case of character regression.

Perhaps a more representative work began as a public interest question, that a play could illustrate thru the relations of a small group in the appropriate setting. Ayckbourn asked himself why do we have a political system, in which councillors and MPs are selected from those who put themselves forward? The very fact, that they do, seems almost a disqualification for the job. The most suitable may be those who dont impose themselves on others. The play is based on this premise.

Ayckbourn used to go on boating holidays, once with his children, he doubted would forgive him. Manning a boat does not require a license. Boats dont have brakes. The consequences can be imagined. He had seen a boat trapped sideways in a lock gate blocking everyone else.

A family on a boat will have its 'captain', usually Dad. Mum is stuck down in the galley, doing the same job she has been doing all year, on what is supposed to be her holiday. The children are press-ganged as deck hands.

In the play, the complement is, at first, two couples. One man puts himself forward as the leader. But another couple join and there is a coup leading to a dictatorship. It turns out that the couple who never assumed control were really the most suited to do so.

The setting is surely the most famous of all Ayckbourn's plays, the cabin

cruiser in the fibre glass tank, that inevitably leaked thousands of gallons of

water, causing chaos both at the usual premier venue in Scarborough and when

the play moved to London.

At the latter fused theatre, Ayckbourn found himself alone in the dark,

guiltily pondering the damage and thousands of cancelled tickets.

He cheers up at the thought that they must have forgiven him, because, years later, two of his plays were staged, at the same time, in two of London's leading theatres. As they were nearby, Ayckbourn confesses to a rare bout of vanity, waiting for the two audiences to stream out into the sun-shine and rhapsodising: Theyre mine...all mine!

Richard Lung.

To top.