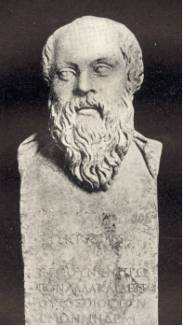

I WILL begin the praise of Socrates by comparing him to a certain statue. Perhaps he will think that this statue is introduced for the sake of ridicule, but I assure you it is necessary for the illustration of truth. I assert, then, that Socrates is exactly like those Silenuses that sit in the sculptors' shops, and which are holding carved flutes or pipes, but which when divided in two are found to contain the images of the gods. I assert that Socrates is like the satyr Marsyas. That your form and appearance are like these satyrs, I think that even you will not venture to deny; and how like you are to them in all other things, now hear. Are you not scornful and petulant? If you deny this, I will bring witnesses. Are you not a piper, and far more wonderful a one than he? For Marsyas, and whoever now pipes the music that he taught (for it was Marsyas who taught Olympus his music), enchants men through the power of the mouth. For if any musician, be he skillful or not, awakens this music, it alone enables him to retain the minds of men, and from the divinity of its nature makes evident those who are in want of the gods and initiation: you differ only from Marsyas in this circumstance, that you effect without instruments, by mere words, all that he can do. For when we hear Pericles, or any other accomplished orator, deliver a discourse, no one, as it were, cares anything about it. But when anyone hears you, or even your words related by another, though ever so rude and unskillful a speaker, be that person a woman, man, or child, we are struck and retained, as it were, by the discourse clinging to our mind.

If I was not afraid that I am a great deal too drunk, I would confirm to you by an oath the strange effects which I assure you I have suffered from his words, and suffer still; for when I hear him speak my heart leaps up far more than the hearts of those who celebrate the Corybantic mysteries; my tears are poured out as he talks, a thing I have often seen happen to many others besides myself. I have heard Pericles and other excellent orators, and have been pleased with their discourses, but I suffered nothing of this kind; nor was my soul ever on those occasions disturbed and filled with self-reproach, as if it were slavishly laid prostrate. But this Marsyas here has often affected me in the way I describe, until the life which I lived seemed hardly worth living. Do not deny it, Socrates; for I know well that if even now I chose to listen to you, I could not resist, but should again suffer the same effects. For, my friends, he forces me to confess that while I myself am still in need of many things, I neglect my own necessities and attend to those of the Athenians. I stop my ears, therefore, as from the Sirens, and flee away as fast as possible, that I may not sit down beside him, and grow old in listening to his talk. For this man has reduced me to feel the sentiment of shame, which I imagine no one would readily believe was in me. For I feel in his presence my incapacity of refuting what he says or of refusing to do that which he directs: but when I depart from him the glory which the multitude confers overwhelms me. I escape therefore and hide myself from him, and when I see him I am overwhelmed with humiliation, because I have neglected to do what I have confessed to him ought to be done: and often and often have I wished that he were no longer to be seen among men. But if that were to happen I well know that I should suffer far greater pain; so that where I can turn, or what I can do with this man I know not. All this have I and many others suffered from the pipings of this satyr.

And observe how like he is to what I said, and what a wonderful power he possesses. Know that there is not one of you who is aware of the real nature of Socrates; but since I have begun, I will make him plain to you. You observe how passionately Socrates affects the intimacy of those who are beautiful, and how ignorant he professes himself to be, appearances in themselves excessively Silenic. This, my friends, is the external form with which, like one of the sculptured Sileni, he has clothed himself; for if you open him you will find within admirable temperance and wisdom. For he cares not for mere beauty, but despises more than anyone can imagine all external possessions, whether it be beauty, or wealth, or glory, or any other thing for which the multitude felicitates the possessor. He esteems these things, and us who honor them, as nothing, and lives among men, making all the objects of their admiration the playthings of his irony. But I know not if anyone of you have ever seen the divine images which are within, when he has been opened, and is serious. I have seen them, and they are so supremely beautiful, so golden, so divine, and wonderful, that everything that Socrates commands surely ought to be obeyed, even like the voice of a god.

At one time we were fellow-soldiers, and had our mess together in the camp

before Potidaea. Socrates there overcame not only me, but everyone beside, in

endurance of evils: when, as often happens in a campaign, we were reduced to

few provisions, there were none who could sustain hunger like Socrates; and

when we had plenty, he alone seemed to enjoy our military fare. He never drank

much willingly, but when he was compelled, he conquered all even in that to

which he was least accustomed: and, what is most astonishing, no person ever

saw Socrates drunk either then or at any other time. In the depth of winter

(and the winters there are excessively rigid) he sustained calmly incredible

hardships: and amongst other things, whilst the frost was intolerably severe,

and no one went out of their tents, or if they went out, wrapped themselves up

carefully, and put fleeces under their feet, and bound their legs with hairy

skins, Socrates went out only with the same cloak on that he usually wore, and

walked barefoot upon the ice: more easily, indeed, than those who had sandaled

themselves so delicately: so that the soldiers thought that he did it to mock

their want of fortitude. It would indeed be worth while to commemorate all that

this brave man did and endured in that expedition. In one instance he was seen

early in the morning, standing in one place, wrapt in meditation; and as he

seemed unable to unravel the subject of his thoughts, he still continued to

stand as inquiring and discussing within himself, and when noon came, the

soldiers observed him, and said to one another -- "Socrates has been standing

there thinking, ever since the morning." At last some Ionians came to the spot,

and having supped, as it was summer, they lay down to sleep in the cool: they

observed that Socrates continued to stand there the whole night until morning,

and that, when the sun rose, he saluted it with a prayer and departed.

I ought not to omit what Socrates is in battle. For in that battle after which the generals decreed to me the prize of courage, Socrates alone of all men was the savior of my life, standing by me when I had fallen and was wounded, and preserving both myself and my arms from the hands of the enemy. On that occasion I entreated the generals to decree the prize, as it was most due, to him. And this, 0 Socrates, you cannot deny, that when the generals, wishing to conciliate a person of my rank, desired to give me the prize, you were far more earnestly desirous than the generals that this glory should be attributed not to yourself, but me.

But to see Socrates when our army was defeated and scattered in flight at Delium was a spectacle worthy to behold. On that occasion I was among the cavalry, and he on foot, heavily armed. After the total rout of our troops, he and Laches retreated together; I came up by chance, and seeing them, bade them be of good cheer, for that I would not leave them. As I was on horseback, and therefore less occupied by a regard of my own situation, I could better observe than at Potidaea the beautiful spectacle exhibited by Socrates on this emergency. How superior was he to Laches in presence of mind and courage! Your representation of him on the stage, 0 Aristophanes, was not wholly unlike his real self on this occasion, for he walked and darted his regards around with a majestic composure, looking tranquilly both on his friends and enemies: so that it was evident to everyone, even from afar, that whoever should venture to attack him would encounter a desperate resistance. He and his companions thus departed in safety: for those who are scattered in flight are pursued and killed, whilst men hesitate to touch those who exhibit such a countenance as that of Socrates even in defeat.