This is not a discussion for the experts but for people who know as little as me, if possible. Tho, timely comment would be welcome. Paul Harrison's book The Third World Tomorrow showed why the expensive expert must make way for amateurs sufficiently trained to meet the essential needs of all in society, not just a rich elite. If they dont, relief for the very poor is postponed indefinitely.

Harrison also pointed out the lessons for our over-developed Western models of society. Besides his book, I reviewed the relevance of general training in essentials to Britain's over-strained health service and education system. Also, these and other public services, as well as businesses, are beleaguered by bureaucracy.

This page gives two more examples ( computer programming and legal redress ) of the general need to make practical knowledge more freely available.

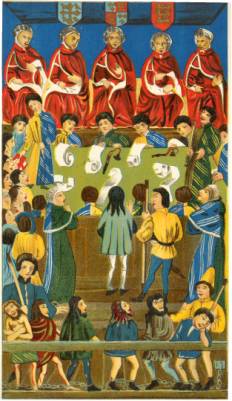

The Law has been called 'the oldest closed shop of them all'. For instance, there have been complaints about the minimal redress from the Law Society of complaints about members of its profession.

A century earlier, in Bleak House, Dickens frankly stated that the

cause of 'the law's delay' ( as Shakespeare called it ) is that it pays.

Henry Fielding was a majistrate as well as a novelist. In Tom Jones, he has a character foolishly desire to sue, till her husband remonstrates that it would put a job the way of their lawyer relative, but it wouldnt do them any good.

Nowadays, Britain has a 'Citizen's Charter' to ensure standards of civil service. You would think scenarios, like the following, might be avoided.

Your small claims case eventually comes up for trial, after some few months. You hope it wont take more than an hour, at lawyers' charges. But the judge decides it will take longer. The judge adjourns the case, for a later date in the crowded court time-table. On the second hearing, the judge can't decide to give a verbal verdict in court. A good while later, a written verdict is made. You fail to get the refund, you already took several months trying to obtain from the firm.

The judge gives the defending firm yet another chance to make amends, on their terms. But the firm is so big and busy that they fail to collect the product for re-servicing. The defendant had said they would do the servicing in their own time. But they took so long, theyd evidently over-looked you.

You go back to the court and claim the cost of servicing, to be done by some other firm. The judge, at least, has allowed for this in his verdict. But it costs you another fee. You claim this cost, too, which wakes up your seller vehemently to refuse to pay it, while promising to collect the product for re-servicing.

Meanwhile, you are put under pressure to give-in to the seller, because their local court has not collected the payment from them, such as the verdict gave you a right to, if the seller didnt service the product.

The claimant's local court told you, the claimant, to come back if you didnt receive the service from the defendant. But when you return to your local court, you are told, instead, to write to the defending firm's local court to collect the default payment for defendant's failure to service.

After several letters and months later, the defendant's local court tell you, the claimant to go back to your local court to make the request. Only on the prompting of your local court does the defendant's court pay the verdict's default payment, plus court fee for having to demand it.

At some point in this run-around, that the courts give the claimant, a staff member apologises, tho she is undoubtedly one of the few people in the whole dismal affair, you find no fault with. However, some man doing business with the court, at the same time, over-hears, and not minding his own business, puts in a good word for the court system. His dismissive manner, about any need for the court to apologise, suggests a cosy relationship with them. No doubt, some people do very well out of the system, if not those who it is meant for.

We are talking about eighteen months failed attempts to get a resolution to a sub-standard sale, either on one's own terms or even the defendant's terms.

Traditionally, the law has been regarded as the friend of the rich. At the age of five or so I was told that you should never have anything to do with lawyers. They werent for ordinary folk. No justice could be expected from them -- only fees one couldnt afford.

Eventually, the law was changed for the less well-off to take minor complaints to court, without incurring heavy costs. Or that was the theory of 'small claims courts'. The practise can turn out differently. In my second letter to the Wakeham report, such considerations were part of a case for constitutional reform.

Here, I wish to warn the ordinary citizen of possible pit-falls to being

one's own civil lawyer, say, in seeking recompense for faulty goods or poor

service, of the kind brought up on the consumer watch-dog television and radio

call-in programs.

The Daily Mail ran two online computer issues on the subject of: Does

anyone care about the poor customer? The press depends on lavish advertising

by chain retailers, who may have been investigated, more than once, as a

monopoly. So, this verdict, after a flood of consumer sob stories, was not

idle.

Supposing one, whom the gods would destroy, is mad enough to risk taking a claim to court. There are several things to consider before one begins. Firstly, is one's claim just? Was the person or firm, one is making a claim against, given a proper chance to make redress or compensate one or make reasonable amends? Does one's grievance really demand the drastic step of going to court? In general, has one got a good conscience about one's business dealings? Has oneself been fair in one's dealings with the defendant, one is claiming against?

To test one's claim, one can seek an appointment with the Citizen's Advice Bureau. If they are not impressed, a judge or arbiter is unlikely to be. You may also learn, there, what law to plead with. In the first instance, advice may be about getting the firm to act on your complaint without necessarily having to go to court. Other help may get you to marshall your arguments, making them forceful and to the point.

( Much to the advisers' displeasure, the courts may try to use them as unpaid lawyers for the citizen claimant, facing the professionals in the small claims court. )

Is there a law that unambiguously says claimants, or plaintiffs, are within their rights, say, to return sub-standard goods or have a refund for bad service? If you are taking on some big multiple firm, they will have a department of lawyers, just to cope with people like you. You have to give them proper notice that if they dont give customer satisfaction, then you may take legal action.

They may not settle. Their reply may state the relevant Act of Parliament that covers your case. This may be a consumer protection act. But you dont take their word for it. Remember, your opponents' lawyers are the professionals and know all the tricks. You are the amateur, whose first time mistakes can and will doom your case. Instead, youve contacted the Trading Standards Officer. After youve explained your complaint, he may tell you, even before you ask, the exact act upon which your affidavit or formal complaint must be based.

You may find that the most relevant act is an amended version, more strongly in your favor than the original act. So, in this instance, you would follow the trading standards officer's advice of submitting your affidavit under a given consumer protection act as amended. This amendment might involve giving the customer a longer time to return faulty goods, whose state is not apparent at first.

Of course, your big corporate opponent knows all about this. As a matter of course, any complaints you make back to their store may be met with frustration and delay. The longer you can be kept with the product, you are unhappy with, the more your consumer rights are eroded. The worse the service, the less strong your legal position to claim redress.

The firm's staff may be nice enough people but, as just one more customer, you may be fair game in the battle to maintain their turn-over, profits and jobs, to earn the living we all seek.

Perhaps one of the worst mistakes of the amateur lawyer is to assume that

all you have to do is present all your arguments and the judge will see you

have an over-whelming case. More likely, he will be over-whelmed by all the

verbiage and miss the most important points, in his decision, when it is too

late to correct him. Judges have mountains of evidence to traverse in their

jobs and cannot be expected to remember everything about your little

grievance. You have to guide the judge on the best trail thru your case, so he

doesnt lose his way to your main points.

The lesser points can be appended to your main statement, in case they are

needed to answer questions put by the judge or defending lawyer.

Having searched one's conscience whether one is really in the right, just as crucial is whether one has the evidence to prove it. If one cannot make a convincing case, there is no point in wasting one's money prosecuting it. Dont be beguiled by small claims court leaflets saying one doesnt need the kind of cast-iron case required for a full court of law.

More to the point, the leaflets insist that, for any technological product

which fails to meet standards, the plaintiff or claimant will need an expert

report made independently of one's own influence. It musnt be from family,

friend or employee. This is expensive. In the late nineties, you would have to

pay a computer expert £40 per hour for the report. A richly paid English judge

may think you should have had him on hand in court -- still at £40 per hour.

If you wanted a lawyer to handle your case, that was then £80 per hour.

You will pay the going rate, anyway, for hiring the judge. If you lose the

case, that fee is forfeit. In answering your summons to court, the firm's

lawyer may ask the judge for compensation of at least that amount,

at the claimant's expense.

Well might you say: I thought this was supposed to be a small claims

court!

But that is not the end of the expenses, the small claimant may be up against. There is no rule that the big firm may not bring its own employed expert witness. There really does seem to be one law for the little man and another for big business. But a few firms so dominate the market, it hardly seems worth going to another one's expert staff. None of them are likely to side with the public.

The claimant may consult a small independent business for expert advice but

it is not in their interest to go against the giants of their industry. Even

so, before the case comes to court, the defendant may try to dissuade the

claimant from seeking independent advice, expecting the customer to trust

their own qualified employee. And that, despite the fact that the law denies

the dissatisfied customer any use of dependants or associates for expert

advice.

It is like a battle of wills, in which the defendants try to take over your

case and conduct it on their own terms.

The firm also sends its own lawyer, who asks the judge that travel expenses of up to several hundred pounds also be awardable to his firm against the claimant. Presumably, the courts know that if claimants had to pay these travel expenses to go to the firm's local court, most people far from London, or wherever, would waive their statutory rights. The courts would lose much business and justice would be seen not to be done but to be localised.

The defendant firm may even use your case as a chance to run in a trainee lawyer, scribbling down the proceedings, as if his livelihood depended on it. That is three against one in the court room and your opponent is a provider of employment to the system you are being adjudicated under. The firm's lawyers are one of them, as far as the profession of judges is concerned. Moreover, the firm's expert is another professional, whose opinion might well also be deemed of more weight than the amateur claimant.

In all probability, the judge admittedly knows nothing about the

technicalities of a given case. He readily turns to the only expert on hand,

that of the defending firm, which may have been the way they wanted things all

along. It may be that the claimant's mass of evidence simply does not weigh,

in the judge's mind, against expert testimony. However much the defendant's

expert may stand on his dignity, the claimant's case becomes only as good as

his opponent's technical witness allows it to be. Like a politician, he has to

decide whether or not it is prudent to buck his firm's party line, at all.

What claimant would wish to so put himself at the mercy of his opponents?

We live in a culture of professionalism. The small claims court is an experimental intrusion of amateurs, which judges may not think much of. Law and technology, in their ways, are highly qualified occupations. He may feel that the man in the street gets no more than he deserves for intruding into the preserve of specialists. The amateur may be regarded automatically as 'no better than he should be.'

We come to the crux of why amateur claims may not work or be allowed to

work. It reminds of local interest groups or communities trying to fight the

decisions of their local authority to welcome some outside 'developer' and

their mega-bucks, like the post-colonialism of some multi-national corporation

draining third world countries of their resources. Supposedly independent

arbitration only seems, to the locals, to rubber-stamp the official case.

Such arbitration is like being delivered into the hands of one's enemies.

The claimant only wanted to return his purchase and get his money back, or

claim a refund from a service that failed to deliver its promises. But his

little contest seems to imply much more. It becomes an indictment of the

claimant. He is cross-examined by the defending lawyer and occasionally by the

judge.

If he answered all the questions, he may still find to his surprise and

chagrin that a judge's written verdict slights his evidence, and even his

character, over a matter that could have been simply cleared up, were there

any opportunity to do so. Some more tact may be required of a judge, here.

This is an issue distinct from the question of lodging an appeal against the judge's decision. The sums involved in a small claim dont justify re-trial.

While the whole point of the courts is that two contending parties agree to defer to a judge or arbiter's decision, the judge may defer to the authority of the large firm's expert. For instance, a computer firm lays down the law that it will only refund or replace sold items that have hardware faults but not if they only have software faults or 'problems' -- they tend not to use words like 'faults'.

There is nothing in English consumer law to justify this distinction. A

fault is a fault. Yet the judge can over-rule statute law and may go along

with computer firm law. After all, they are the experts, arent they?

Indeed they are. And judge and novice computer buyer dont know anything to

contradict them. But it turns out that software 'problems', to use the

euphemism, may not be so straight-forward. Apparently, one reason is, in a

phrase, closed source software.

Anyone who has built a web site knows that to

change the look of it, you have to view its source page. But you cannot do

that with the almost universal Microsoft Windows Operating System. Its source

is closed.

In general, computer programmers had best be able to see the source of the software, its actual logical structure, to debug it. At any rate, the actual writer of a program is in the best position to put it right. It turns out that computer specialists may not find correcting software programs a routine job. They are liable to charge you a couple of hours just to look at it, all at full rates, without promising results afterwards.

A joke about why hackers, under false pretences, obtained Microsoft's source codes is that Windows has so many bugs in it, they were driven to desperate measures to put them right. At one point, the Microsoft corporation was reported -- by The Guardian -- as saying that Linux was ( their ) public enemy number one. It's code author jokingly talks about 'world domination'. Linux is an open source operating system. Dont ask me more. Obviously, I arent a programmer. But I havent the slightest doubt that the future is with open source. Tho, at the time of writing, even Linux seems not yet user-friendly enough to become the norm for unskilled home users.

If they were wise, Microsoft would make their Windows Operating System into open software, while theyre still ahead. Otherwise, we have the same old story of the supposed advantage of an imposed uniform standard over the creative freedom to modify.

The conflict may be compared with the dead hand of convention that rests on

English spelling, in all its aberrations, which leave so many illiterate.

Similarly, the availability of open source operating systems or other

programs would allow people to learn better how they work. Rather than

treating computer programs as magic, more people would become accustomed to

see their logic. Program-literacy would be stimulated.

The moral, once again, is the need to spread important skills, like advocacy or programming, thru-out society. The spread of literacy made writers less of an exclusive profession. Technological advances are likely to repeat this creative enfranchisement in the visual and musical arts. The same needs to be done, in essentials, for all the professional skills that largely affect society.

Richard Lung.